Image Credit: William Hogarth, “The South Sea Scheme” (ca. 1721), The British Museum

Note: This is an expanded version of my recent Wall Street Journal article “Born of Boom and Bust.” It is a long post, because I’ve been fascinated by this engraving my entire adult life.

The most unforgettable image of the South Sea bubble — the topic of my recent Back in Business column — is a masterpiece by the British artist William Hogarth.

Under a turbulent sky full of whirling clouds, an entire city is going mad. A public square in London teems with hundreds of people, gambling, picking each other’s pockets, beating and whipping each other. A crowd hauls a giant wooden lever that turns a creaking merry-go-round, on which speculators from all walks of life straddle horses shaped like phalluses. Satan himself, flames spewing from his mouth, presides over the pandemonium.

Everywhere in Hogarth’s image, the natural order of things is subverted:

People creep and crawl along the ground; wolves slink high in the air.

Clergymen in their holy robes — a priest, a rabbi, and a minister — gamble at the commoners’ game of “pitch and hustle,” squatting in the dirt, as far away as they can get from the tiny dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral peeking out from the opposite end of the city.

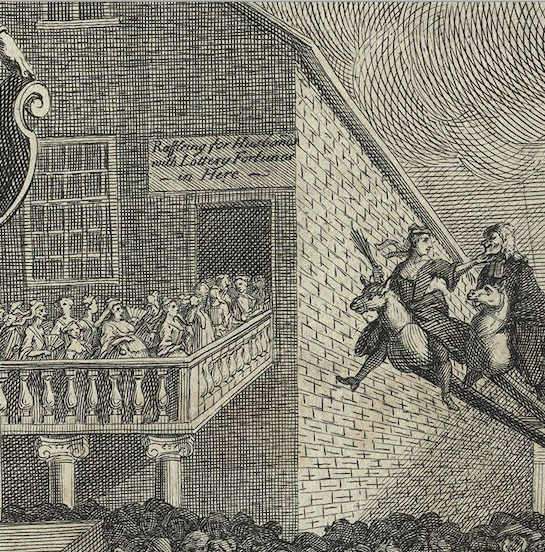

Buildings and architectural features run helter-skelter through space, wrenching the rules of artistic geometry. In the left background, the balcony of a building swarming with women tilts crazily downward, teetering toward a vanishing point impossibly high in the sky.

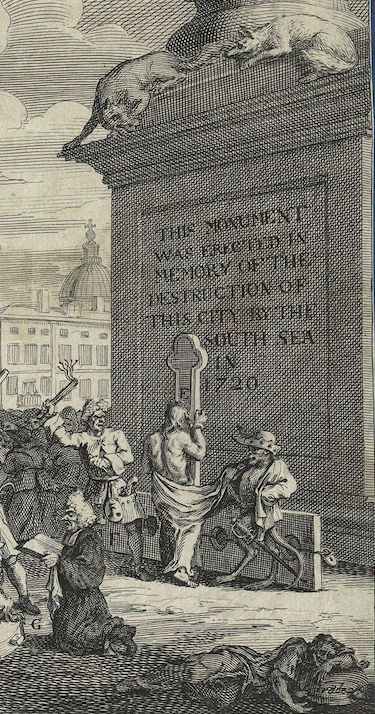

The square itself doesn’t exist; it is a composite of the space in front of Guildhall (shown at the left, where Satan stands) and the Monument to the Great Fire of London (whose base dominates the right of the scene). The plane of the square pitches sharply down toward the foreground, as if at any moment this swarm of lunatics would spill into our laps.

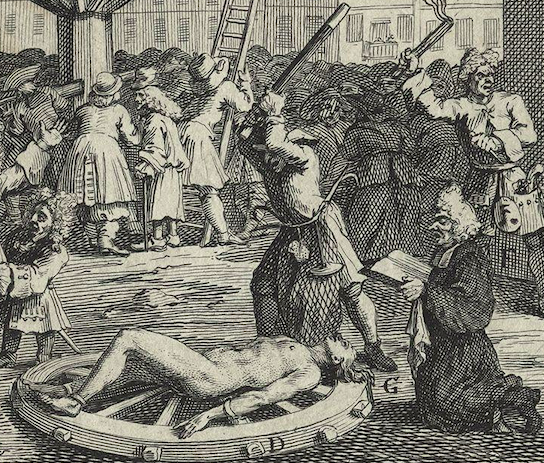

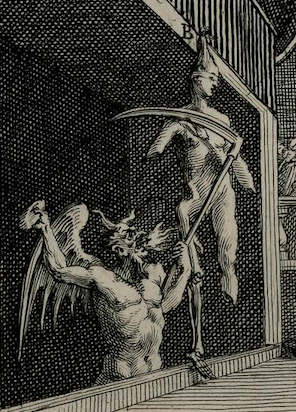

A figure of “Vilany” (villainy) flogs “Honour” with a cat-o’-nine-tails as a monkey in an elegant naval uniform bares Honour’s back for the lashing.

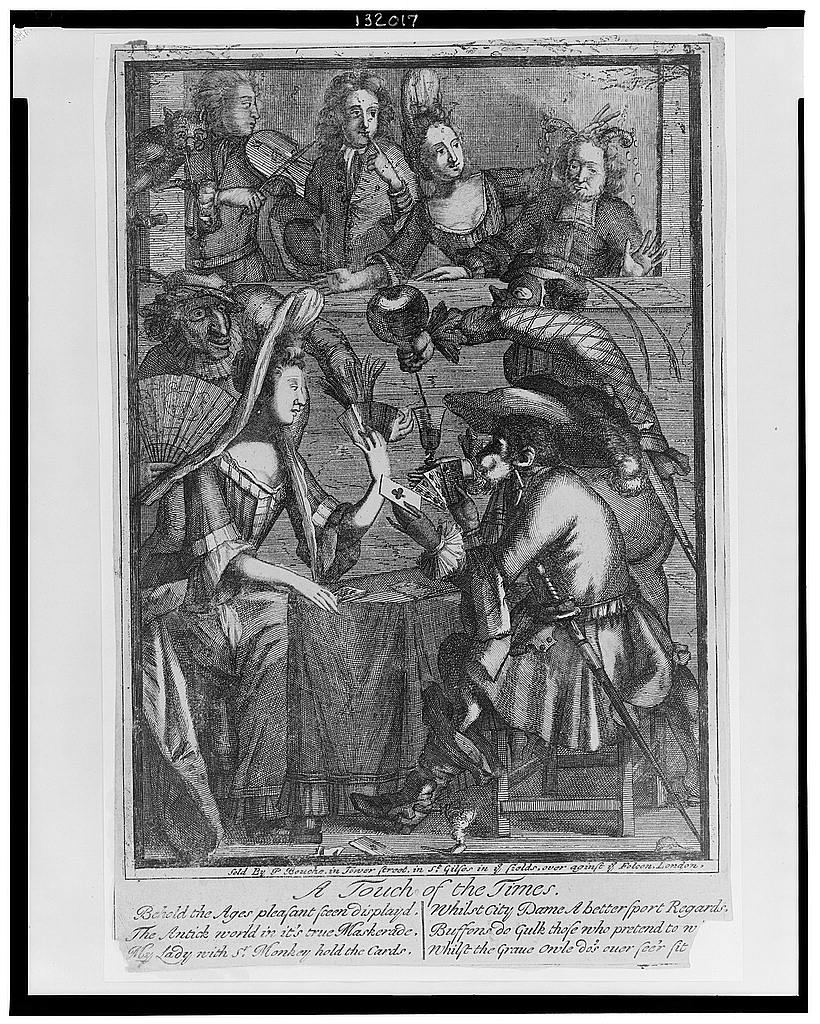

Hogarth may have based his flamboyant monkey on this anonymous satirical print from 1720:

Monkeys had long been a symbol of mimickry, folly, and greed. Jan Brueghel the younger’s “Satire on Tulip Mania,” ca. 1640, portrays speculators in the Dutch tulip bubble, which had burst in 1637, as a crowd of drunken, gluttonous simians.

Nearby, still another minister chants from a book of prayer as “Self-Interest” bludgeons “Honesty,” who is strapped to a giant wagon wheel.

Hogarth may have based this vignette on Albrecht Durer’s famous woodcut of the martyrdom of St. Catherine of Alexandria, who was broken on a wheel before she was beheaded:

Meanwhile, Satan has turned Guildhall, the administrative seat of London’s government, into a meat market. Screaming to the crowd in words of flame, he hacks the goddess Fortune to pieces and heaves chunks of her bloody flesh to the mob.

A righteous-looking Quaker, too dignified to chase after the body parts, holds open a burlap sack in modest hopes of catching some — or, perhaps, he is waiting for money to fall from the sky.

Behind him, a dwarf and a liveried footman pick the pockets of a schoolmaster, from whose belt hangs a hornbook, used to teach young students the alphabet. Some scholars have argued that the dwarf is the great poet Alexander Pope, who stood 4’6,” had invested heavily in the South Sea bubble, and had badgered his friends to join him.

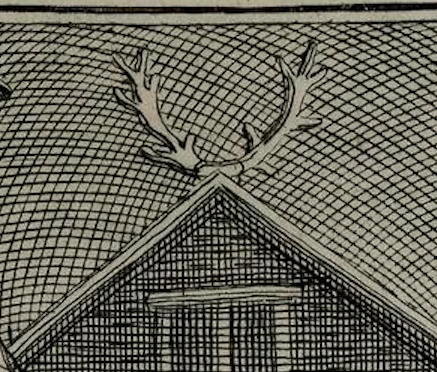

The building on whose crazy balcony the women stand in search of a lottery-winning husband is crowned with a huge rack of stag antlers, which symbolized lust and cuckoldry.

In Greek and Latin myth, the goddess Diana transformed Actaeon, the hunter who who lusted after her, into a stag with giant horns. She then sicced his own hunting dogs on him; as they chased him through the woods, his antlers caught in the underbrush and the dogs devoured him. Poems on this theme were popular in English literature. Horns were thus a symbol not only of lust but of over-reaching behavior that led to disaster.

For decades, a pole topped by stag antlers stood at a spot along the Thames known as Cuckold’s Point or Cuckold’s Haven in the village of Charlton, then on London’s eastern outskirts. Charlton hosted a lusty annual celebration known as Hornfair. The artist Samuel Scott showed this historic location in a riverscape he painted around 1750-60, now in the collection of Tate Britain:

In this detail from Scott’s painting, the pole rises from a pyramidal wooden base next to the stairs that lead down to the river’s edge. An impressive pair of antlers, almost identical in size and shape to the pair in Hogarth’s engraving, perches on top of the pole. This symbolic landmark would have been familiar to nearly everyone in London at the time.

So the stag’s antlers, at the very pinnacle of Hogarth’s composition, tower over the town to remind the viewer that the lust for money had supplanted love and sex in people’s lives; marriages were being destroyed not by sexual adventures, but by greed.

Hogarth suggests that the damage from speculation may be irreversible: The gigantic monument at the right says it was “erected in memory of the destruction of this city by the South Sea,” while the goddess of Trade (legitimate industry), hollow-eyed and clothed in rags, cowers in the lowest corner, starving in the dark.

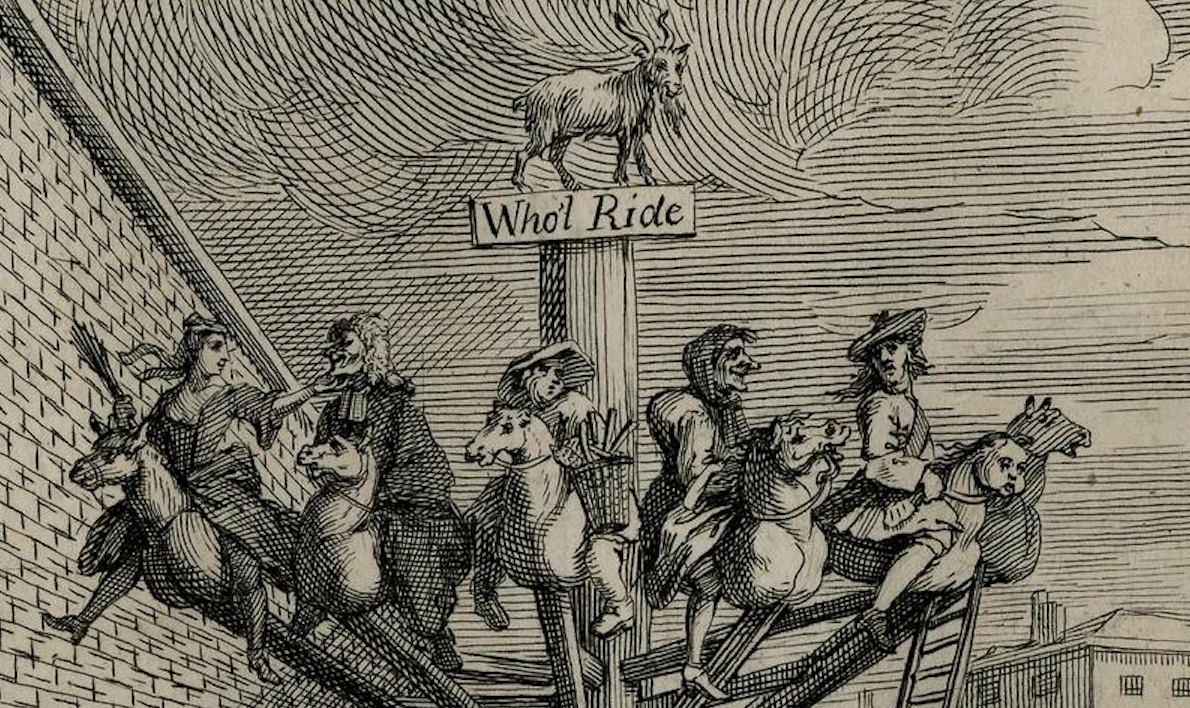

Above all looms the creaking, hulking, haunting merry-go-round, a contraption that could even give Stephen King nightmares.

At its top is a goat, representing Pan, the Greek god of chaos and panic, whose rampant horns visually echo the stag antlers on the building to the left. Under the goat a sign asks “Who’l Ride” (Who Will Ride?).

The carousel animals are all truncated horses, shaped suggestively like rampant penises: The riders are literally getting the shaft. Hogarth renders them as distinctly identifiable individuals from all walks of life: from left to right, a prostitute with her beauty mark, a minister, a shoeshine boy, an old hag with a hunchback, and a Scottish nobleman. The Scotsman’s horse, hauntingly, has the face of a human girl, who is weeping:

Far below, an aristocrat in a top hat, desperate to climb aboard, shoves a ladder into the carousel at an impossibly dangerous angle.

The sign “Who’l Ride” is one of the keys to understanding Hogarth’s image.

In “riding,” or “horsing,” 18th-century brokers, or “stock-jobbers,” subdivided lottery tickets or shares of stock and rented them out to speculators, often for only a few hours at a time. (Day trading is not a modern invention!) No wonder all the animals on the merry-go-round are horses.

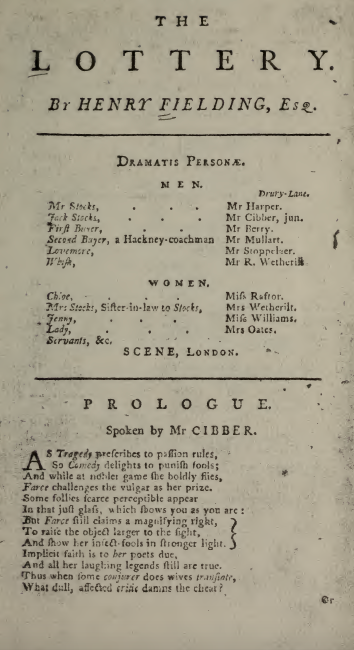

The Lottery, a musical comedy written by Henry Fielding and first produced in 1732, describes how a “ride” on a “horse” worked.

This snippet of dialogue is between Jack Stocks, a cynical stock-jobber who deals in lottery tickets and company shares, and Buyer No. 2, his second customer of the day:

2 Buyer: Does not your Worship let [rent] horses, Sir?

Stocks: Ay, friend.

2 Buyer: I have got a little money by driving a hackney-coach, and I intend to ride it out in the lottery.

Stocks: You are in the right; it is the way to drive your own coach.

Mr. Stocks then sings:

These are the best horses

That ever ran courses;

Here is the best pad for your wife, Sir;

[He] Who rides once a day

If luck’s in his way

May ride in a coach all his life, Sir.

When the hackney driver asks to buy a ticket with the same number as his carriage license, Mr. Stocks tells his assistant, Mr. Tricks, to assign him that number whether it’s available or not: “As the gentleman is riding to a castle in the air, an airy horse is the properest to carry him.” Fielding and Hogarth were close friends, and the writer may well have had Hogarth’s sky-high merry-go-round in his mind when he wrote that line.

Mr. Stocks then opens his door to find an elegant woman waiting to see him. She proclaims: “I am come to buy some tickets, and hire some horses, Mr. Stocks. I intend to have twenty tickets and ten horses every day.” Because she is wealthy, she can afford to buy tickets outright, but she still wants to ride horses, too, by trading fractional interests.

The sign “Who’l Ride,” then, doesn’t merely ask who will take a joyride on the merry-go-round. It is explicitly asking who will day-trade fractional shares in the South Sea Co.

And Hogarth’s answer is everyone.

The merry-go-round resembles a giant wooden wheel of fortune.

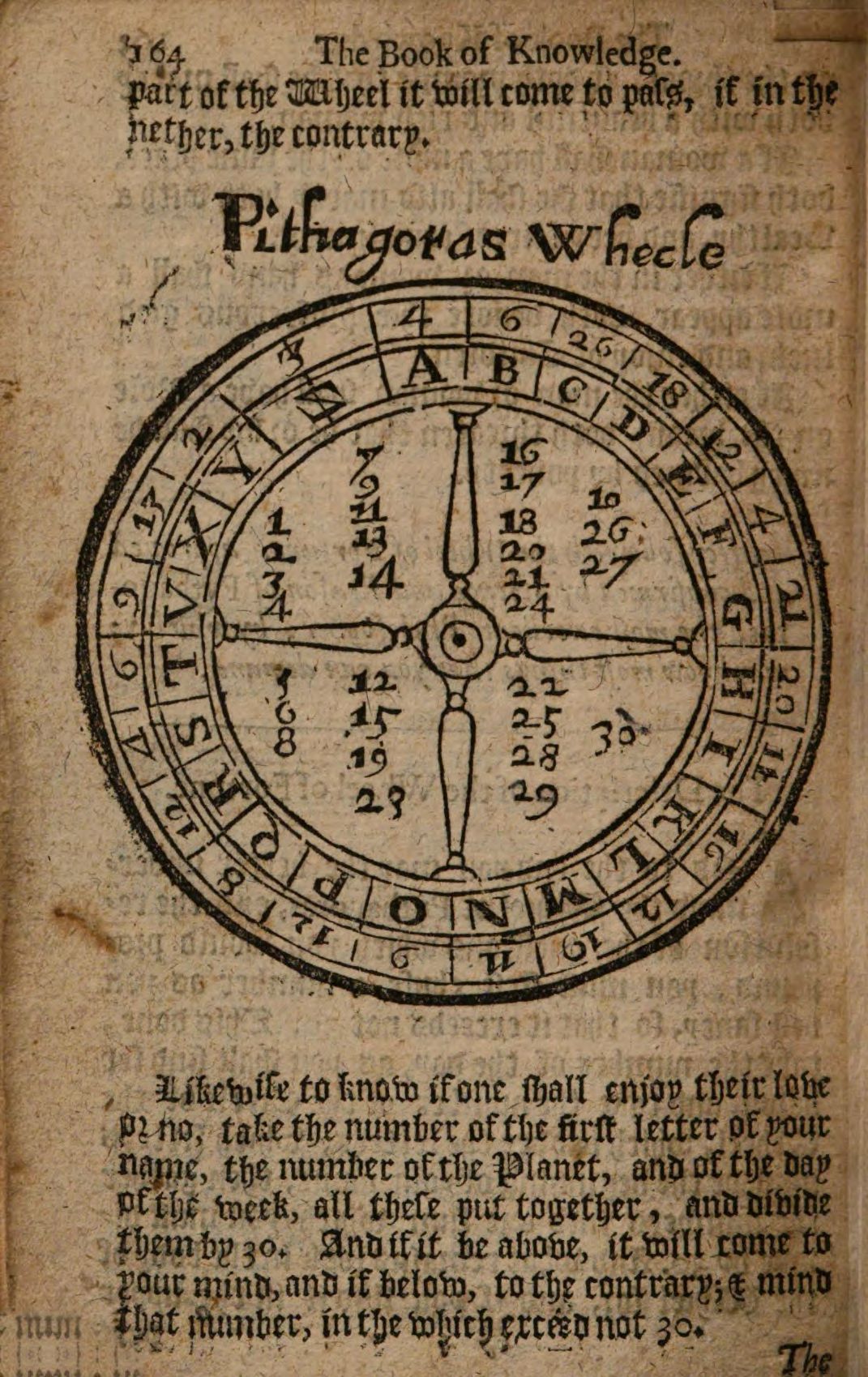

Wheels of fortune were widely used at the time to predict the future. In the 1676 edition of a popular almanac by “Godfridus,” The Knowledge of Things Unknown, Shewing the Effects of the Planets, and other Astronomical Constellations, With the strange Events that befal the Men, Women, and Children, born under them, several pages explain how to use a “Wheele of Fortune” purportedly patterned after discoveries by the mathematician Pythagoras:

Among the destinies the wheel could predict, according to Godfridus, were “If it shall be a plentiful year,” and “If a man shall be fortunate in his house,” and “If a person shall be always rich or poor.”

Thus the riders on Hogarth’s wheel may symbolize not only the variety of people who speculated in the South Sea bubble, but the range of their destinies: Depending on where the wheel stopped spinning, some might end up destitute, prostituting themselves, or as smug and rich as ever.

Fortune, in its mingled meanings of both “luck” and “wealth,” runs like a fugue through Hogarth’s image. The merry-go-round that dominates the composition is echoed in the foreground in the wheel upon which Honesty is being broken. At the left, the goddess Fortune, nailed to the wall by her hair, is being butchered by the devil. The sign above the door on the balcony thronging with women reads: “Raffleing for Husbands with Lottery Fortunes in Here.”

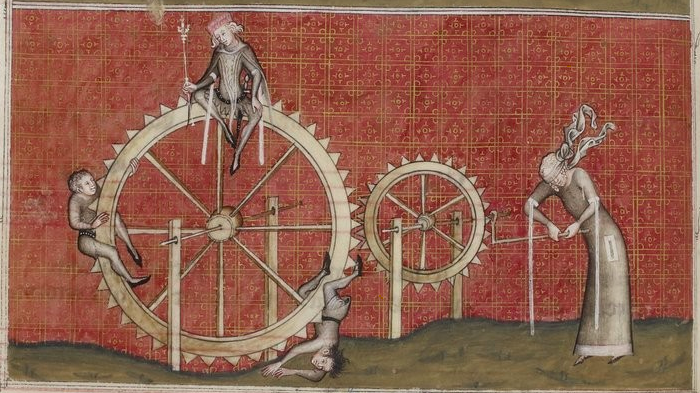

Furthermore, the crowd beneath the merry-go-round is turning it by pushing a giant wooden lever. Into at least the 16th century, religious plays were staged across Europe with mechanical wooden wheels of fortune as a stage prop to symbolize how fickle luck and wealth are without divine grace. Three actors portraying kings would climb the wheel at the bottom, surmount it at the top, and fall off it from the middle as an actress representing the blind and capricious goddess Fortuna turned a crank that propelled the wheel. This representation, from a mid-14th-century French manuscript, is typical:

Hogarth’s immense wheel of fortune is, instead, rotated by the mob itself as people shove the crankshaft around with their arms and shoulders.

Although I have no idea if Hogarth ever read it, this scene reminds me uncannily of one of the greatest passages in Dante’s Inferno:

Qui vidi gente piu ch’altrove troppa,

Here I saw many more people than anywhere else,

e d’una parte e d’altra, con grand’urli,

and from one end to the other, with great heaves,

voltando pesi per forza di poppa.

they rolled boulders by pushing them with their breasts.

Percoteansi incontro; e poscia pur li

They kept going until they crashed into each other,

si rivolgea ciascun, voltando a retro,

then turned around and rolled the weight back again,

gridando: ‘Perche tieni?’ e ‘Perche burli?’

hollering ‘Why save?’ and ‘Why spend?’

Cosi tornavan per lo cerchio tetro

Like this they revolved in a terrible circle

da ogni mano all’opposito punto,

from one end back to the opposite side,

gridandosi anche loro ontoso metro;

hollering again their mocking chorus;

poi si volgea ciacsun, quand’era giunto,

then, having reached the other end,

per lo suo mezzo cerchio all’altra giostra.

each rolled back in his half-circle to the other jousting post.

In Dante’s vision, the human race — greedy and miserly by turns — has so tightly embraced the fickle nature of Fortune that the goddess no longer needs to turn her wheel. In the pursuit of wealth, people have become the wheel, rolling back and forth for all eternity. Even if Hogarth didn’t know this passage from Dante, he envisioned it brilliantly in his own right.

The caption-poem at the bottom, with specific features in the scene pinpointed by Hogarth with capital letters, reads:

See here ye Causes why in London,

So many Men are made & undone,

That Arts, and honest Trading drop,

To Swarm about ye Devils Shop [A]

Who Cuts out [B] Fortunes Golden Haunches,

Trapping their Souls with Lotts & Chances

Shareing em from Blue Garters down

To all Blue Aprons in the Town.

Here all Religions flock together,

Like Tame & Wild Fowl of a Feather,

Leaving their strife Religious bustle,

Kneel down to play at pitch & Hussle, [C]

Thus when the Sheepherds are at play,

Their flocks must surely go Astray;

The woeful Cause [tha]t in these Times,

[E] Honour, & [D] honesty, are Crimes,

That publickly are punish’d by

[G] Self Interest, and [F] Vilany;

So much for Monys magick power

Guess at the Rest you find out more.

price 1 Shilling

A century later, the great British essayists William Hazlitt and Charles Lamb praised Hogarth beautifully. Hazlitt:

He does not represent folly or vice in its incipient, or dormant, or grub state; but full grown, with wings, pampered into all sorts of affectation, airy, ostentatious, and extravagant. Folly is there seen at the height — the moon is at the full; it is “the very error of the time.” There is a perpetual collision of eccentricities — a tilt and tournament of absurdities; the prejudices and caprices of mankind are let loose, and set together by the ears, as in a bear-garden.

Lamb:

His graphic representations are indeed books: they have the teeming, fruitful, suggestive meaning of words. Other pictures we look at — his prints we read.

…merriment and infelicity, ponderous crime and feather-light vanity, like twi-formed births, complexions of one intertexture, perpetually unite to show forth motley spectacles to the world…. the works of Hogarth, so much more than those of any other artist, are objects of meditation. Our intellectual natures love the mirror which gives them back their own likenesses.

Hogarth is believed to have produced this engraving in 1721, when the wounds from the bursting of the bubble were still raw. (He didn’t publish it until 1724, perhaps because the competition from satirical Dutch prints was too intense until then.) Only 23 years old, the impressionable artist caught the mood of a city — and nation — caught up in collective madness. When Hogarth was a young boy, his father, a lexicographer and Latin teacher who struggled to provide for his family, spent four years in debtors’ confinement. That, and the vivid contrasts between rich and poor in London’s booming economy, fired Hogarth’s lifelong contempt for greed.

Some people, when they hear “the circle of life,” probably think first and foremost of The Lion King. I think of Hogarth’s giant wooden wheel creaking in the sky, bearing its riders around and around in an eternal loop of greed and folly.

Further reading

Jenny Uglow, Hogarth: A Life and a World

Benjamin Graham, The Intelligent Investor

Jason Zweig, The Devil’s Financial Dictionary

Jason Zweig, Your Money and Your Brain

Jason Zweig, The Little Book of Safe Money

South Sea Bubble 1720 Project, Yale School of Management’s International Center for Finance

South Sea Bubble Resources, Baker Library, Harvard Business School